Living and Breathing Plants

Closing the Gap between Plant Science and Policy

Chapter 1

I peered closer at the brown lesions that appeared between the veins. An official diagnosis would take a few days, but it was clear that death was imminent.

Pleased with the results, I smiled.

Author Angela Records inspecting a shipment of live plants at the USDA-APHIS

facilities at the Port of Los Angeles, as a guest, looking for

invasive species.

On the stainless steel counter, lit by natural light from the row of windows that flanked one wall of the laboratory, were about a half-dozen clear, four-inch round plastic vessels, each containing a similar specimen of Phaseolus vulgaris—green beans. Though we are most familiar with the fruits of this plant, the leaf, too, is edible, and the dry stalks of the plant can be used as animal fodder. As a PhD candidate at Texas A&M University, I was studying the disease known as bacterial brown spot, examining the processes by which it attacks the leaves, pods, and stems of infected plants.

Although I have never been overly fond of green beans, my satisfaction did not come directly from the fact that my specimens were dying. I found monitoring the small changes that occurred as the disease attacked the plants to be fascinating. More importantly, I knew that the results of my experiments on how the bacterial brown spot pathogen infects plants could help farmers and gardeners stave off the disease. I recorded my observations in my lab notebook and put the specimens back in the incubator.

Eleven years later, I have traded long days in the laboratory for equally long days working in and around the nation’s capital. But my obsession with plant diseases remains intact.

I live and breathe plants. Technically, we all do. Without plants, we’d have no oxygen to fill our lungs, no clothing to fill our closets, no medicine to fill our bathroom cabinets, no food to fill our pantries. But how many of us roll out of bed in the morning (from under sheets and comforters made of plant fibers) and say, “Thank you, plants”? How many of us pull on a favorite T-shirt, sit down to eat a bowl of cereal, and reflect on the science that went into protecting the cotton and wheat crops from pests and pathogens?

Theobroma Cacao (“food of the gods”) By Francisco Manuel Blanco (O.S.A.).

Ancient cultures and religions often centered on agriculture. Festivals coincided with planting and harvest cycles, a tradition still carried on by many indigenous peoples around the world. Even many of the scientific names of plants still carry the mark of the ancient gods and goddesses with whom they were once associated. Dianthus, the scientific name given to the carnation, translates as “the flower of god,” while Theobroma, the genus containing the cocoa tree, translates to “food of the gods.” Zeus, Aphrodite, Venus, Artemis—they, too, show up in the scientific names of a variety of plants. Agave, the mythological namesake of the genus of spiny plants that includes those from which tequila is made, was a fierce goddess who tore her own son to pieces, believing he was a lion.

A continued tradition of agriculture worship would certainly make my current job easier; I’m a consultant for Eversole Associates, a small agriculture, science, and technology advocacy firm that represents science groups in Washington, DC. If the Pledge of Allegiance were supplemented with, say, a prayer in homage to Demeter, the Greek goddess of the harvest, or to Chicomecōātl, the Aztec goddess of agriculture, plant science advocacy might not seem like such an uphill battle. But some days, I feel like members of Congress are Agave and the programs I fight for are the mythological son— unknown and about to be torn into tiny pieces.

Chapter 2

September 7, 2011, was one of those days. Time was running out for Congress to pass the budget for the 2012 fiscal year, and the Hill had become the site of fierce and ongoing debates. I had been assigned the task of escorting a group of scientists from the National Plant Diagnostic Network (NPDN) to the Capitol, where we would meet with representatives from their home states to argue for the program’s funding to be restored. The NPDN, a system of U.S. diagnostic laboratories established in 2002 to mitigate the impacts of plant pests and pathogens, had achieved a number of important successes in its nine years of existence. So NPDN scientists had been taken by surprise when, three months earlier, the version of the budget passed by the House zeroed out the successful program’s already minimal funding. My boss, Kellye Eversole, the head of Eversole Associates and a former professional staffer for the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, had received a call; could we assist the scientists in representing their interests to Congress? We rallied our forces and scheduled a number of meetings on the Hill for the four professors who flew in from various universities around the nation. But it was down to the wire—the Senate would be releasing its agriculture budget that afternoon, either echoing the House’s decision or opting to renew funding. Working in our favor was the fact that the ensuing battle to reconcile the two budgets could stretch on for weeks, even months. We needed to find support from as many members of Congress as we could.

Dressed in my most convincing suit and a pair of black heels, I grabbed an umbrella from the hall closet before shutting the oak door of my quiet two-story home in the DC suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland, and hurrying to the nearest Metro stop. As the rain blew at me from all directions, I tried not to read the incoming storm as a sign of what the day might bring. One might expect a preacher’s daughter would be free of such superstitions. Of course, one might also expect that a preacher’s daughter wouldn’t be a scientist and a devout believer in evolution. But with annual visits to my grandfather’s farm in East Texas, it didn’t take me long to realize that God was, at the very least, not the only one contributing to our welfare and survival.

The author on her first advocacy visit, a graduate student intern with the APS Public Policy Board, in the USDA conference room in Washington DC.

As I settled into a seat on the Metro, I began to review my documents for the morning’s briefing. Normally, Kellye would have joined me for the meetings we had scheduled with Senators Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), Carl Levin (D-MI), and Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), and Representatives Mike Thompson (D-CA) and Sam Farr (D-CA), but she was out of town for a conference on wheat genomics. Nervous, but also excited about the opportunity, I paid little attention to the influx of passengers around me.

Thankfully, the L’Enfant Plaza Metro stop is directly connected to the hotel where the scientists had spent the night, so I could avoid the rain. I spotted the four scientists in the hotel lobby right away, having met each of them over the years at meetings of the American Phytopathological Society—a professional organization for plant pathologists. After we exchanged greetings, I offered a short rundown on congressional meeting etiquette:

- Do stay on topic.

- Don’t fall asleep in a meeting.

- Don’t take a phone call during the meeting.

While these seemed like obvious instructions, I had seen each of these rules violated in previous meetings on the Hill. On one infamous occasion, during a long day of back-to-back meetings with congressional staffers and agency officials, a senior scientist in our group had begun snoring in a slightly-too-warm conference room in the USDA Whitten Building, waking only after multiple throat clearings and nudges from the rest of us. Wanting to make sure they made the biggest impact possible on their visit, the NPDN scientists listened earnestly as I reviewed the protocol, and then, briefcases in tow, we stepped out into the rain and piled into a taxi heading for the National Mall to inform our elected representatives about the importance of plant diagnostic science.

Chapter 3

Every day, in fields and forests across the nation, plants are under attack by pests and pathogens. Thousands of plant pathogenic microbial species and insect pests are native to the United States, and many more are invasive, entering the country through trade and bearing the potential to quickly decimate large portions of the nation’s 914 million acres of farmland as well as natural environments unprepared for their advances. The Mediterranean fruit fly, the Asian citrus psyllid, sweet orange scab, chilli thrips, rice cutworms, plum pox, and Asian soybean rust are only a few of the killers that American farmers have dealt with over the past decade. My client, the NPDN—which coordinates laboratories and experts nationwide and offers training and education in plant disease diagnostics and crisis response—has helped avert the spread of dozens of high-priority plant pests and pathogens, ensuring the safety of our food supply, protecting the livelihoods of the more than two million people who work in the agriculture industry, and saving millions of taxpayer dollars in the process. And yet, despite its successes, the program’s $4.4 million annual budget was now at grave risk of being cut, putting America’s fields and forests—not to mention the nation’s $742.6 billion agricultural industry—in danger.

Brilliant minds in laboratories everywhere can work to improve the science of plant diagnostics, but without government backing, the majority of these successes can’t be implemented.

In the thirteen years I spent training and working as a plant pathologist, I spent many days traversing Texas in a pickup truck to participate in farmer diagnostic training sessions; traipsing through agricultural fields from California to Maryland looking for spots, streaks, specks, wilts, cankers, lesions, and ooze; or running experiments in laboratories to learn how microbes attack plants at the cellular level and how best to stop them. Back when I was grinding up plant leaves to extract DNA, placing bits of plant tissue on Petri plates to observe microorganisms living therein, and studying the genomes of bacteria that cause plant disease, I certainly would not have predicted that one day I would trade in my dusty Dr. Martens and lab coat for a polished wardrobe more suited for meetings with members of Congress. But I had come to learn that science works in mysterious ways. Brilliant minds in laboratories everywhere can work to improve the science of plant diagnostics, but without government backing, the majority of these successes can’t be implemented. The first step toward getting the backing that scientific programs need is making people aware that plant diagnostics is much like human diagnostics. When it comes to infectious diseases, whether hosted by humans or plants, it is much easier to prevent a widespread outbreak than it is to stop one that has already begun. So when a post-doctoral fellowship turned into an opportunity to work in the nation’s capital, spreading awareness about outbreaks and prevention, I jumped at the chance.

As the taxi driver wove through the steady stream of traffic headed in the direction of the National Mall, I thought about the various pathogen outbreaks I had studied over the years. I wondered how many of these stories were known by members of Congress. The story of Florida’s most recent battle with citrus canker, which began several years before the NPDN’s founding, was legendary among plant pathologists. But how many policy makers outside of the state of Florida knew about it?

It started on September 28, 1995, when Louis Francillon, a forty-one-year-old agronomist for the Florida State Department of Agriculture, stood outside a house on Southwest 16th Street in Miami-Dade County, performing his routine inspections. Sweating in the afternoon heat, Francillon carefully inspected a triangular flytrap hanging from a branch of a sour orange tree. He was looking for Mediterranean fruit flies—exotic pests that cause extensive damage to a variety of fruit crops, including citrus. No fruit flies were in the trap. As he turned away, however, a nearby grapefruit leaf, backlit by the sun, caught his eye. In the center of the leaf, surrounded by the bright green glow of chlorophyll, was a brown lesion bordered by a yellow halo.

Photo Courtesy of Timothy Schubert, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org – See more at:

http://www.ipmimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1262020#sthash.KX0QOwaI.dpuf

Francillon pulled his magnifying lens out of his pocket, attempting to shield his eyes from the sun’s glare as he took a closer look. He knew instantly what he had discovered. The lesion was a telltale symptom of citrus canker, a disease that had originated in Southeast Asia but had spread through agricultural trade to citrus-growing regions around the world. It had been found in Florida in 1912 and 1986, and had been successfully eradicated both times. This time the state would not be so lucky; by the time of Francillon’s discovery, the pathogen had already begun to spread. This made containment difficult.

For the next seven years, Florida’s Department of Agriculture waged war on the bacterial invader in an effort to protect the state’s $9 billion citrus industry, but the disease persisted. Many growers went out of business. Others let go the majority of their employees. With the economy suffering and the threat of statewide crop damage looming, the legislature came up with a solution: cut everything down. Every citrus tree within 1,900 feet of an infection had to go. By 2002, crews were traversing the state, felling trees at a pace that peaked at five thousand per day. In all, 16.5 million trees in groves, nurseries, and backyards were destroyed—so many trees that, if stacked end to end, they would have reached nearly one third of the way to the moon.

But despite these extreme measures, it was too late. The disease had been spreading for nearly a decade when Mother Nature, in the form of a series of hurricanes, carried the disease well beyond infected groves. With all hopes of containment now thwarted, the $1.6 billion eradication program—the largest plant disease eradication program in U.S. history—was ended in 2006.

A more recent disaster came in the form of a small insect. The emerald ash borer—a flat-headed, metallic-green insect, native to Asia and Eastern Russia but found outside of Detroit in 2002, the same year the NPDN was created—is just one of many dangerous “hitchhikers” that have slipped into the United States in wood-packaging materials. Appropriately shaped like a small bullet, the ash borer has killed nearly a hundred million ash trees in eighteen states, from Kansas to Maryland, sweeping through urban areas and suburbs, where ash is commonly planted. As with citrus canker, eradication efforts led to wide-scale tree removal. In some neighborhoods, every tree was taken out in one fell swoop, with only rows of stumps and sawdust left behind. A recent study published by the American Journal of Preventive Medicine connected this rapid depletion of the natural environment with increased rates of death from heart attacks and lung disease. Across the fifteen states in the study area, researchers drew connections between tree loss caused by the emerald ash borer and more than 20,000 deaths.

The emerald ash borer. Photo Courtesy of The Cornell Plant Pathology Photo Lab. http://www.ppath.cornell.edu/PhotoLab/

The NPDN was established to mitigate the impacts of these and other pest and pathogen attacks. Although the program was not created in time to curb the ash borer’s initial devastation, it has since developed training materials to prepare scientists, gardeners, and others to identify signs of emerald ash borer infestation. The first detection of the pest in Minnesota, in 2009, was a direct result of NPDN’s training program. This early detection led to a state quarantine that has thus far been effective in protecting Minnesota’s trees.

Had the NPDN been established prior to citrus canker’s spread, Florida’s story could also have unfolded differently. With a cadre of NPDN-trained first responders, perhaps the disease would have been spotted even before Francillon’s identification, leading to an earlier and more focused response. It’s hard to say what might have happened. But the NPDN was put into place in order to prevent new outbreaks from having similar consequences. And yet, the program’s successes in doing so had apparently gone unnoticed—a catch-22 that those of us working in agriculture advocacy often face.

Compared to the impacts of cancer and other diseases on our everyday lives, it’s easy for plant diseases like citrus canker to seem insignificant.

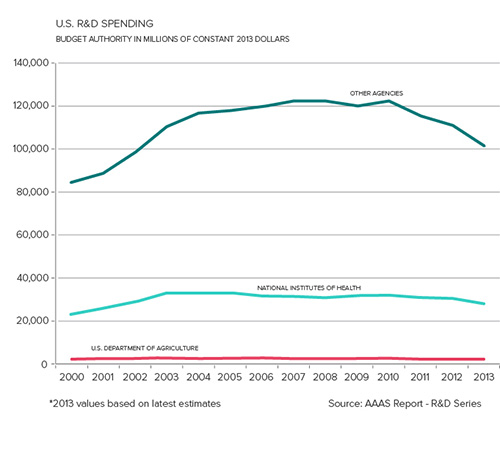

The U.S. agriculture industry has largely been successful. It has kept our nation’s grocery stores stocked with a ready supply of food, a state of affairs that most of us take for granted. And without looming threats of food shortages or compelling stories, plant and agriculture programs all too frequently take a back seat to the numerous other activities with which they compete for federal funding. After all, the human-interest aspects of many other programs are often more readily apparent. For example, all of us, including members of Congress, have been sick, and most of us have also lost loved ones to illness. Because we can all relate personally to the need for medical advances, convincing voters and Congress to fund medical science is not a particularly hard sell, and, therefore, funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) not only remains secure but rises almost annually. Compared to the impacts of cancer and other diseases on our everyday lives, it’s easy for plant diseases like citrus canker to seem insignificant. And so, over the past fourteen years, while NIH funding has risen steadily, from $22.9 billion in 2000 to $28.5 billion in 2013, funding for U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) science programs, already a small percentage of the amount NIH receives, has declined from $2.4 to $2.2 billion. But despite this much smaller level of funding, agricultural science continues to be responsible for many crucial successes on which our food supply, our jobs, and even our lives depend. I hoped the NPDN scientists and I would be able to remind Congress of this important fact.

Chapter 4

“Hello, are you the Plant Network?”

Still glancing at his schedule, where the name of our group was printed, a man with a dark goatee and receding hairline entered the reception area where the five of us sat awaiting our 1:30 meeting.

“I’m Troy Phillips, Congressman Sam Farr’s Senior Legislative Assistant.”

“The National Plant Diagnostic Network, or NPDN for short,” I interjected, rising quickly to my feet and extending my hand to begin a round of handshakes and introductions. As we followed Troy into Congressman Farr’s office, settling into plush chairs surrounding an ornately carved coffee table, I began by expressing our gratitude for the Congressman’s support.

“We would like to thank the Congressman for his commitment to promoting agriculture research,” I said. Although every meeting begins with such pleasantries, I sometimes deliver them through clenched teeth, politely “thanking” members of Congress for their support when in reality they’ve done quite the opposite. This time, I meant it. Congressman Farr is the Ranking Member of the Appropriations Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, and Food and Drug Administration, and I was happy that in this meeting, we would likely find a sympathetic audience. It was our third meeting of the day, and we were all beginning to get a little edgy as we waited to hear the Senate’s version of the agriculture budget.

“The main reason for our visit today,” I continued, “is to provide you with information about the NPDN and answer any questions you may have.” Then I jumped to the point: “Funding for the program has been zeroed out in the House budget,” I said, motioning the way a baseball umpire calls a runner “safe.” I glanced over at NPDN’s executive director, Rick Bostock, a UC Davis expert in canker, brown rot, and other fungal fruit diseases. Right on cue, he began to describe the program’s significance.

The author with Rick Bostock (center) and Jim Stack (right) in the Russell Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill.

“During an outbreak of plant disease, a timely response is critical,” he began, in the practiced tone of a seasoned professor. “Two things need to happen: you must identify the ‘positive’ plants and clear the ‘negatives.’” (Echoing the language we use to talk about human viruses and other infectious agents, “positive” plants refer to those that have been infected by a certain pathogen; “negatives” are the plants that have not.) “If the NPDN is not around to help with that process, retailers may go out of business waiting to be cleared to resume plant sales,” Rick explained, referring to the USDA-mandated sales freeze that is levied on plants suspected of harboring particularly worrisome pathogens. “Or, even worse, the outbreak may go unchecked with no NPDN-trained ‘first responders’ to report it,” he added.

I looked across the table at Troy, who reminded me of a younger and better-looking Billy Bob Thornton, searching for signs that Rick’s words were making an impact.

Each day, Troy and other legislative aides, senators, and representatives hear hundreds of requests from constituents and the more than 12,000 registered lobbyists in DC. The lobbyists—along with countless special interest groups, like the National Education Association, Citizens United, and AARP, as well as lesser-known groups, like the U.S. Association of Reptile Keepers, the Balloon Council, Cigar Rights of America, and the American Pyrotechnics Association—regularly descend on Capitol Hill like starving persons at a soup kitchen.

Some of these groups let their money do the talking. Take the National Rifle Association, for example, which spends more than $3.4 million per year on lobbying efforts and campaign contributions, or the American Civil Liberties Union, which spends $2 million. But smaller groups, like the American Phytopathological Society (APS), can’t rely on endorsements to sway congressional opinion in their favor. Such groups have to rely on their membership—plant pathologists, in the case of APS—to voice their concerns to Capitol Hill.

I continued to watch Troy’s reaction as Jim Stack, a regional NPDN director and specialist in the diagnosis and management of field crop diseases in the Biosecurity Research Institute at Kansas State University, took his turn. Jim emphasized the marked improvement in crisis response established by the NPDN. “Prior to the NPDN, information on new pests and diseases was not easily accessible, communications on new outbreaks were poorly coordinated and inadequate, and infrastructure supporting plant diagnostics in the country had degraded,” he explained. Before the NPDN was established, scientists in Nebraska, for example, may or may not have been aware of a disease discovery in neighboring Iowa. And training in plant disease diagnostics was limited to a handful of experts, making it far more difficult to identify and combat diseases before they were already established.

For every pathogen or pest that slips through the system, many more are prevented from spreading—but these kinds of stories rarely make the headlines.

Jim leaned forward from his blue leather chair and slid an informational packet across the table to Troy. “The NPDN is an example of a government success,” he stated. The word lingered in the air like pollen in springtime as we waited for Troy’s response.

While the media often capitalizes on disasters like the emerald ash borer, or Florida’s battle with citrus canker, agricultural programs also stop many disasters from happening. For every pathogen or pest that slips through the system, many more are prevented from spreading—but these kinds of stories rarely make the headlines. Can you imagine what this would look like?

“Plum Pox Found in Routine Inspections. Nothing Happened.”

“Beetles Stopped at USDA Checkpoint. Invasion Averted.”

I might read these stories. But I’m not sure many other people would or that I would blame them if they didn’t. When agriculture is successful, to the eyes of the public, nothing seems to be happening. Crops keep producing, trade ensues, and we continue to have food on our plates. In the absence of a disastrous outbreak, what is there for anyone to notice?

But in this era of endless budget cuts, we couldn’t allow NPDN, and its important work, to remain unnoticed. We had to make a case that Troy would remember and pass on to the Congressman.In my time working in advocacy, I have learned that the fastest way to a member of Congress’s heart is by demonstrating the impacts of a given program on his or her constituents. Congressman Farr’s district included 88,000 farms and ranches nestled in California’s central valley and fertile coastal regions and $43.5 billion in agricultural sales in 2011. His support could go a long way toward ensuring the program’s future, and we had come prepared with stories about NPDN’s impacts on the state.

“You’re familiar with sudden oak death?” Jim asked. Troy nodded his head “of course.” The disease, characterized by oozing cankers on trunks, foliage dieback, and, eventually, the death of infected trees, had heavily impacted California’s stately oaks. In 1995, the microbial menace passed through coastal California forests, attacking the many native oak species, disrupting the natural ecosystem, and leaving swaths of ugly brown tree skeletons in its wake. I knew this was our chance to make the importance of the NPDN hit home. Jim began to tell the story.

A hillside in Big Sur, California, devastated by sudden oak death.

In March of 2004, biologists from the California Department of Food and Agriculture, conducting routine inspections at several large wholesale nurseries in southern California, discovered that their camellias and rhododendrons were infected with a fungus-like microbe, Phytophthora ramorum—the pathogen that causes sudden oak death. Like its cousin, Phytophthora infestans, which wiped out potato crops in the mid-1800s and contributed to more than one million human deaths in Europe, P. ramorum is a serious threat—and it doesn’t just infect oak trees, but rather is spread through a number of hosts. I could tell by the light in Troy’s eyes that Jim’s story had captured his interest.

“By the time of the discovery, plants that had likely been exposed to the pathogen had already been shipped throughout the country,” Jim explained. This was a serious problem; P. ramorum is a “quarantine” pathogen—a blacklisted microbe that triggers U.S. government protocols—and thousands of retailers throughout the country were required to cease business operations. While the jobs of thousands of owners and employees—not to mention the country’s oaks and the habitats to which they contribute—all hung in limbo, retailers sent more than 100,000 samples to the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland, to be analyzed for signs of infection. This caused an even bigger problem. The scientists in the APHIS diagnostics laboratory can process only twenty to twenty-five samples per day.

Jim paused for impact, vertical lines shooting up his forehead from his furrowed brow. “This was when the NPDN got involved,” he explained to Troy. In an effort to avert a nationwide outbreak of sudden oak death, the NPDN participated in an unprecedented investigation, which utilized already existing diagnostic laboratories at universities across the country to speed up a clearance process that would have otherwise resulted in costly downtime for businesses nationwide. It is estimated that by enabling many nurseries to quickly resume operations, the NPDN saved businesses a collective $20 million. Meanwhile, this intervention allowed APHIS laboratories to focus their energies on the positive samples and their primary objective—preventing the spread of sudden oak death.

Jim sat back in his chair as the other scientists described how the NPDN has since been involved in similar investigations of other pathogens, including plum pox virus and Asian soybean rust, with equally impressive results. And yet, despite these impressive successes, NPDN’s $4.4 million had been zeroed out in the House version of the 2012 congressional budget. A look of astonishment crept across Troy’s face as we continued to offer information on other would-be instigators of disaster and the millions of American jobs that are supported by pest- and disease-free agriculture exports.

“Why would we cut this program?” Troy asked, genuine surprise in his voice as he flipped through the datasheets and pamphlets Jim had given him. He had never heard of the NPDN before, he admitted, expressing his regrets that he didn’t have this information when he was fighting for funding in the House.

I glanced anxiously at the clock over the door. It was already a few minutes past 2 p.m. The Senate was probably revealing its version of the 2012 agricultural budget as we sat there. The day’s meetings—as well as all of the time and resources invested in NPDN over the past decade—would be a lost cause if the budget was ultimately settled and the program’s funding cut.

“In this time of guerrilla warfare, we have to hope for our colleagues in the Senate to help us out,” Troy lamented. “Who have you talked to in the Senate?” he asked, adjusting his silk tie. I described the group’s appointments that day with Senators Feinstein, Levin, and Stabenow, and promised to keep Troy posted as we said our goodbyes.

The group filed out of Congressman Farr’s office, stopping in the hallway to assess the meeting. “I think he gets it,” Rick said. I nodded as I glanced at my schedule and then back at the clock. We still had two more meetings. We could only hope that the other members of Congress and their aides would be as receptive as Troy. But what if we were too late? What if the Senate had already decided to cut the program? Wistfully, I remembered the quiet of the laboratory, where the only fate that directly hinged upon my actions was that of the specimens in my Petri dishes. But as we shuffled down another long hallway to yet another meeting, I received a text from Kellye: NPDN funding had been restored in the Senate budget. Breathing an audible sigh of relief, I excitedly shared the news with the others.

A comparison of NIH vs. USDA R&D funding. USDA receives relatively little funding for R&D.

“Great! We can all go home,” one of the scientists joked. We laughed, some of the day’s stresses beginning to subside.

I knew, however, that the fight was far from over. The budget would come back for conference, at which point NPDN funding could be nixed again. But I had a feeling that Troy would remember our story. He seemed convinced that the NPDN was a program worth saving. Perhaps I should have been content with this, but I couldn’t help but wonder about the fate of other agriculture programs for which Eversole Associates also advocates, ones that lend themselves even less well to a crisis-oriented story. A story of a disease that flattened the nation’s 80 million acres of corn crops would necessarily make headlines and turn policymakers’ heads. Even Demeter and Chicomecōātl would probably roll over in their mythological graves. But when agricultural science works and agricultural pathogens are kept out of the fields, does anyone really notice? We simply expect this, don’t we?

Chapter 5

Two years after our trip to the Hill, the NPDN’s funding remains intact—albeit at an annual level half that of its first eight years of existence. And as I recently placed my overstuffed tote bag on the conveyor belt at the USDA Whitten Building security checkpoint to escort Jim Stack and two other NPDN colleagues to another round of meetings, I felt lucky to have perhaps played a small part in getting the program off the chopping block. But the bigger question still lingers in my mind: who really thinks about plants? Or, perhaps more importantly, who thinks about the science on which our plant production depends?

I am happy that many U.S. agricultural stories are stories of success and that newsworthy disaster stories, like the emerald ash borer and citrus canker, are few and far between. But this may not always be the case. An increasingly global economy means that pathogens and pests are inadvertently shipped all around the world. It also means that the United States and other countries have become codependent for agricultural commodities; thus, disasters that happen elsewhere, like famines in developing countries or the ongoing coffee rust crisis in Central America, can impact us here at home. Sometimes the impacts on the United States are great—the Irish Potato Famine, for instance, resulted in mass migration that forever changed U.S. demographics. Other times, they seem small—like Central American outbreaks of coffee rust that add a few extra cents to the price of your morning latte. As humans, we depend on plants; by extension, we depend on plant science to ensure that our forests are healthy and our crops are productive. It is incumbent upon those of us working in plant science and advocacy to communicate the importance of our work to policymakers and citizens.

Photo Courtesy of Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

http://www.invasive.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5363925#sthash.pRhlllik.dpuf

And yet, even were we all to begin our days with expressions of gratitude for plants and plant science, this alone would not be enough. Plant science needs to transcend university walls and research laboratories, and travel beyond the pages of scientific journals and textbooks. A recent study in Physics World found that the average journal article is read by only three people. Clearly, the gap between scientific output and public awareness is immense. Closing this gap will require scientists continually to remind policymakers and the public that the science that goes into agricultural production is far more complex than the old adage “eat your vegetables” might imply.

But scientists generally prefer to focus on, well, science. And I don’t blame them. The joy of discovery, the satisfaction of proving a hypothesis others never considered, the pleasure of sharing your findings with respected experts in your field—it’s easy for this to feel like enough. While working in the laboratory, I frequently danced down the hallway, proclaiming victory after an experiment revealed interesting results. But these same results don’t send members of Congress dancing down Capitol Hill’s hallways. In fact, too often—as was the case with the NPDN prior to our visits—scientific successes, in particular, go unnoticed. For this reason, it is critical that scientists maintain a dialogue with policymakers so that important programs do not fall through the cracks. Public policy provides the framework for decision-making. But informed policy is what ensures that we continue to make the right decisions.

Authors Angela and Roberta viewing specimens at the USDA-APHIS facilities in Los Angeles.

Clearly, not all plant scientists can make the decision I did, swapping in their field boots and lab coats for a career on the Hill. Nor should they. We need people in laboratories, investigating viruses like wheat streak mosaic, which can be devastating to winter and spring wheat crops, and bacteria like Pectobacterium carotovorum, which causes rot in a wide range of plants including potato and tomato. The reality is, though, that more plant scientists should also focus on making others aware of the larger fates that hang in the balance of these findings. While the effects of plant disease may be readily visible to farmers who lose their crops or agriculture workers who lose their jobs, plant pests and pathogens affect all of our lives, sometimes—as in the case of the emerald ash borer— even changing the very air that we breathe. Plants themselves are living, breathing entities on which the rest of our lives depend.

Some people attribute the bounty of the Earth to God’s miracles. Fair enough, I suppose. But as the Nobel Prize-winning plant pathologist Norman Borlaug put it, “There are no miracles in agricultural production.” The success of U.S. agriculture depends on us all—farmers and workers in the fields, scientists in the laboratories, decision makers on the Hill, and their constituents across the country. Finding ways to make all these groups work together might, indeed, be the real miracle. And it’s a necessary one.